In a new post on ‘Europe in Crisis’, Pamela Ballinger contemplates historians’ responsibilities to provide advice for the present, and offers three lessons from past refugee crises in Europe.

****

In the introductory essay for this blog series, Jessica Reinisch rightly warns against “drawing a straight line between two superficially similar events” and urges that scholars — particularly those making recommendations for policy — proceed cautiously in extracting lessons for today’s migration emergency from Europe’s previous refugee crises. Reinisch does, however, highlight continuities in the motivations, experiences, and responses to refugees, suggesting that studying the past can yield important lessons for both the present and future when translated carefully across differences of time and space. Translation, of course, does not merely entail a mechanical or one-to-one conversion of one language into another but always entails a reinterpretation and what Lawrence Venuti (a key figure in translation studies) has called “the creation of value.” In their respective blog posts on the selective memorializations of past refugee crises in the contemporary Hungarian context, Dora Vargha and Friederike Kind-Kovacs detail the creation (and erasure) of value in previous refugee moments, underscoring the real effects at both the micro and macro levels of these politics of the past for current refugees. As historians, a critical task at the moment lies in translating into present contexts the nuances and complexities of those past refugee emergencies, as well as possible disjunctures and incommensurabilities between past and present. If we do not, we risk ceding the conversation to those who view history merely as a convenient storehouse from which to cherry pick illustrations in support of their particular political viewpoints.

Unprecedented crisis?

Contrary to frequent claims about the unprecedented nature of Europe’s current migration emergency, Europeans possess deep histories of forced migration that could – and should — inform responses to the humanitarian crisis now playing out at Europe’s borders and in its islands, ports, and train stations. In particular, the continent experienced multiple, massive and prolonged refugee “crises” in the last century, especially (but not only) after the two world wars. Indeed, many older Europeans may have experienced such displacement themselves or have family members or neighbors who spent some time as a refugee – whether it be during the Second World War, as a Cold War “escapee” from a communist state, or from the Yugoslav conflicts of the 1990s. It’s not an exaggeration, then, to say that Europe’s 20th century was a refugee century. Although those histories have figured in overly simplistic fashion in the tortuous policy discussions within the European Union, they echo in the forms of grass roots solidarity demonstrated by the many ordinary EU citizens who are working to welcome refugees and provide them with food, accommodation, and medical supplies. In order to stem alarmist fears about being “flooded” by a tide of refugees and to seek durable solutions for those refugees, the New Europe must look back to the history of the old Europe.

In many ways, the modern refugee was a product of the First World War. Although exile and displacement is a story as old as humanity, it was in the aftermath of the Great War that the first international refugee regime arose, housed in the League of Nations. The Norwegian polar explorer and scientist Fridtjof Nansen became the League’s first High Commissioner of Refugees, giving his name to the travel document known as the “Nansen Passport” that facilitated travel for stateless people. The League’s work with refugees focused on Russians displaced by the events of the Revolution and survivors of the Armenian Genocide, as well as the Greek and Turkish populations “exchanged” by the terms of the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne. In the interwar period, international legal protections largely defined refugees in terms of membership in specific groups (e.g. Armenians or Russians).

The events of World War II produced an even more dramatic displacement crisis within Europe. On VE Day in May 1945, an estimated 11 million civilians in Europe had become refugees. (These highly imprecise figures do not include the millions of prisoners of war, as well as the significant numbers of refugees in other parts of the world, such as China.) Displaced persons in Europe included individuals who had been “bombed out” of their homes, those fleeing occupying armies or civil wars, Jewish survivors, and those deported to the Third Reich as forced laborers. These numbers should give pause when we consider the magnitude of today’s refugee crisis and those who claim that Europe lacks the resources to assist those fleeing violence in Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and beyond. In 1945, Europe was a continent in ruins, literally and figuratively. Those Europeans fortunate enough to have survived the war in their homes had very little to give in comparison to citizens of the European Union today, even in light of the Great Recession of 2008.

Within six months of the conclusion of World War II, the Allied forces and the Displaced Persons section of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) repatriated the majority of Europe’s refugees. There remained, however, at least a million or so persons who would not or could not be returned home because there existed a well founded fear of persecution. These displaced persons were soon joined by new refugees coming from the emerging socialist states of Eastern Europe, including Jewish survivors fleeing pogroms in Poland and between 11 and 12 million ethnic German expellees. In the face of these new displacees and the realization that Europe’s displaced persons problem had not disappeared, the International Refugee Organization (IRO) was created, with the aim of finding new homes for those who could not return safely to their countries of origin. (Most of the Volksdeutsche expellees did not meet the eligibility criteria as international refugees and instead received assistance within the two Germanies.)

Palazzo Doria, former barracks for displaced Italians, Fertilia, Sardinia (author’s photo)

Then, as now, the sight of impoverished refugees, many of them markedly different in cultural and religious background from the host countries to which they fled, provoked a mix of negative responses and empathy from local Europeans. Likewise, then, as now, policy makers and personnel at the agencies struggled to figure out who really counted as a refugee deserving of international protection and who, instead, should be considered as merely an economic migrant. These distinctions would eventually be codified in the 1951 Geneva Convention on Refugees, the guiding legal document for the work of the Office of the UN High Commissioner on Refugees established in December of 1950. While the 1951 document built in some ways upon the Convention of 28 October, 1933 Relating to the Status of Refugees, it also redefined the refugee as an individually determined status, rather than an axiomatic consequence of belonging to a specific national group. Article One of the 1951 Convention laid out the criteria of eligibility — most notably “well-founded fear of persecution or reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion” together with displacement outside one’s country of citizenship — that continue to govern international refugee status. However imperfect, many of the international legal frameworks for assisting and managing refugees developed out of Europe’s extended refugee crisis in the 1940s and 1950s.

Lessons

These histories of Europe’s own refugees offer, I would argue, several relevant lessons for dealing with contemporary migratory flows.

First (positive) lesson: resolving Europe’s 20th century refugee crises demanded international cooperation. In particular, resettling millions of Europeans after 1945 required both financial aid (the United States proved the single largest donor for both UNRRA and IRO) and expanded immigration quotas from countries of resettlement (including the U.S., Canada, Australia, and Argentina). In addition, European states like Britain and France sponsored labor migration progammes (“Westward Ho!” and the “French Metropolitan Scheme,” respectively). At the present moment, Australia, Germany, Britain, and France are among those countries that have announced they will take additional Syrian refugees in response to growing public pressure. Despite the announcement of a 30,000 increase in total numbers of refugees to be admitted over the next two years, more pressure must be brought to bear on the U.S to step up and find ways to expedite the vetting process for resettlement. Perhaps members of the U.S. Congress should look back to a historical precedent and send fact-finding missions to European refugee camps similar to those after World War II that turned the tide in favor of passage of the U.S. Displaced Persons Act of 1948.

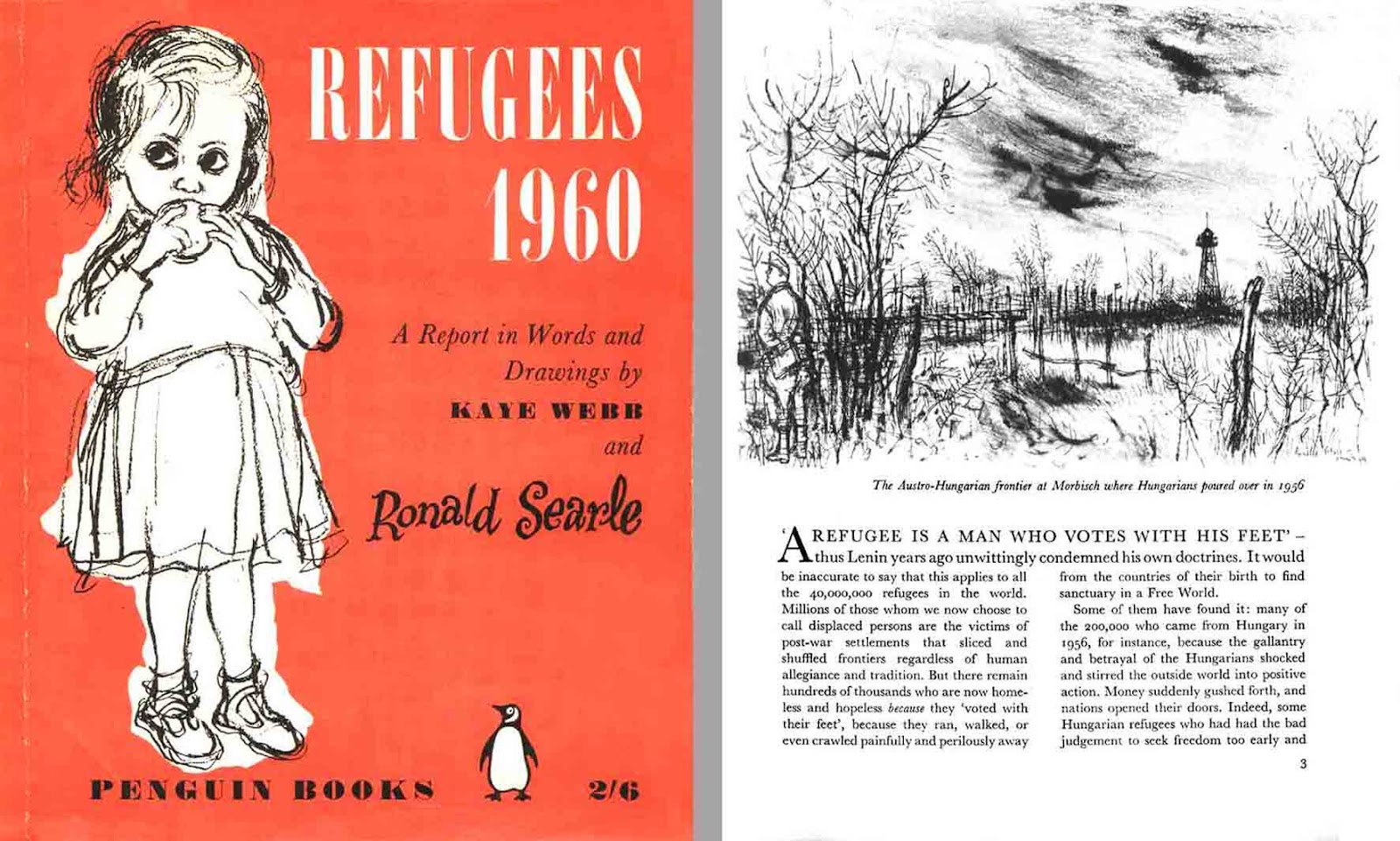

At the same time, however, a second (negative) lesson from Europe’s refugee past is that meaningful and durable solutions are not always achieved quickly. Some refugees in post-1945 Europe languished in camps for over a decade, having been rejected for emigration (often because of illness). This gave rise to the so-called “hard-core” or difficult to settle refugees. Groups in countries like France, the Netherlands, and Switzerland worked to provide new homes for these refugees, particularly those afflicted with tuberculosis. The UN even launched “World Refugee Year” in 1959-1960 with the aim of finally “clearing the refugee camps” in Europe. Given the deleterious effects on refugees of living in limbo for extended periods – as well as the all too real possibilities for radicalization – EU policy makers should do their best to avoid a replay of the story of Europe’s “hard core” refugees who could not find homes.

Refugees 1960: Publication designed to draw attention to Europe’s “hard core” refugees around World Refugee Year

The final lesson for today is one of perspective. However daunting and overwhelming Europe’s refugee problem may appear at this moment, Europeans confronted much greater challenges from internal refugee emergencies in the past and did so in the face of the devastation wrought by war. President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker said as much when he urged his fellow Europeans to take pride in the fact that their continent is today “a beacon of hope,” rather than the ruined landscape of seventy years ago in which Europeans themselves were the refugees.

Eric Hobsbawm once commented, “historians are not prophets,” noting the inadequacy of history (as well as the social sciences) for grasping the assemblage of structures that will constitute future events. Those who study the past, however, are well placed to identify and analyze the past in the present (as legacies, memories, and structural continuities and disjunctures) and to provide critical context, in this case of the current migration emergency in Europe. A critical question remains as to the best venues for doing so. As one response, this blog series draws on (relatively) new media and forms of writing. In what other ways might scholars make critical interventions into the discussion?

Pamela Ballinger is Associate Professor and Fred Cuny Chair in the History of Human Rights at the University of Michigan.

![“Red Cross Relief Donation Arriving to Budapest Train Stations,” 1919.[iii]](http://www.bbk.ac.uk/reluctantinternationalists/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/DSC_1772_2-for-blog-1030x885.jpeg)

![“Child Holiday Train,” 1921.[i]](http://www.bbk.ac.uk/reluctantinternationalists/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/DSC_1867-for-blog-1030x807.jpeg)