Is international humanitarian law in crisis? In this post, Eleanor Davey reflects on the recent history of attempts to amend and enforce the Geneva Conventions.

****

‘Power of Humanity’: this was the slogan of the 32nd International Conference of the Red Cross and Red Crescent, which took place in Geneva from 8-10 December 2015. The conference brought the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the National Societies, and the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFRC) together with governments from the world. These discussions in December demonstrated that ultimately the power of humanity proved less compelling than the autonomy of states. One of the proposals that did not receive endorsement was to create a new platform to improve compliance with international humanitarian law (IHL). It called for ‘a non-binding voluntary mechanism which would bring states together to: 1) exchange information and best practices on key thematic and technical issues, and 2) participate in a voluntary self-reporting process on IHL compliance.’ The ICRC and the Swiss government had been working towards this proposal for several years. While states were keen to express their commitment to the law, they baulked at the idea of a new mechanism to encourage respect for its rules (though ICRC work in this field will continue). After the conference, ICRC President Peter Maurer spoke with frustration about the message that ‘despite the rhetorical recognition that this is a problem, there is no real political will to engage substantively to make things better.’

On the eve of the conference, an IRIN article on the proposed platform offered its final word to Dr Joanne Liu, President of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) International: ‘The [Geneva] Conventions were written to mitigate the impact of war on civilians… and that is what we will fight for, to keep that humanitarian space in war zones.’ As head of an organisation that had lost dozens of staff members, patients, and other civilians in the targeted bombing of their hospital in Kunduz, in northern Afghanistan, Liu held a place of sorry privilege in these debates.

The choice of Liu and MSF’s incinerated hospital to embody the ‘last patch of humanity in a war zone’ was not random; violations of IHL could have been represented by, for example, the barrel bombing of civilians in Syria. Instead Kunduz figures as the most egregious violation in a mass of unacceptable violations, taken as evidence that the lack of respect for international humanitarian law is both long-standing and ever worsening. As Liu declared in a speech shortly after the bombing, ‘This was not just an attack on our hospital – it was an attack on the Geneva Conventions.’

It is striking that the attack on the Kunduz hospital is used to make the case for a more effective mechanism for compliance with international humanitarian law, even as the core of MSF’s response to the attack – a call for the International Humanitarian Fact-Finding Commission (IHFFC) to investigate the incident – appeals to a platform previously created for just this purpose. The IHFFC, established in the late 1970s, was intended to examine alleged violations of the law. However, it has not even once been used. When its creation was being debated, the American jurist Richard Baxter commented that ‘it was somewhat paradoxical to be drafting new law when the old law was not fully implemented and the principal instrument for neutral supervision was moribund.’[1] His words, from 1975, would not be out of place today. The power of humanity has given way to states before.

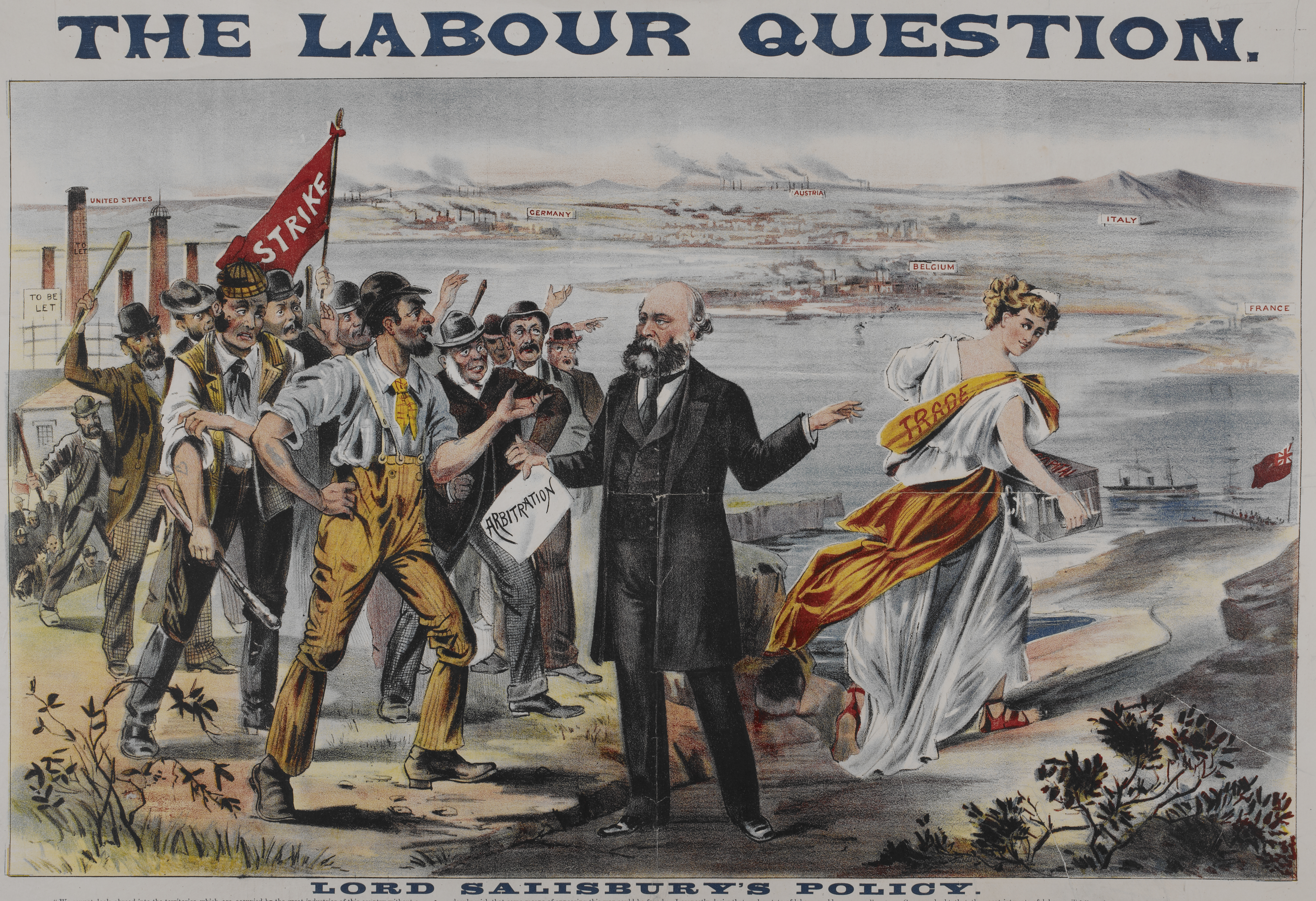

Moreover, claims currently being made about a ‘crisis’ of international humanitarian law strongly echo those made in the 1960s and 1970s, when another so-called ‘crisis’, again brought about by widespread disregard for existing laws of war, led to the writing of Protocols I and II additional to the Geneva Conventions (it was Additional Protocol I that provided for the creation of the IHFFC). Highly destructive wars proliferated nonetheless – in Vietnam, in Pakistan, in Nigeria, in Southern Africa, in the Middle East. But jurists’ and aid workers’ call of ‘crisis’ did not mean humanitarian and human rights norms were afforded a neutral or apolitical space. In the field, humanitarian action was always caught up in political agendas and conflict economies. In the law, a comparable dynamic applied: the Protocols were proposed, drafted and passed in a profoundly political and at times polemical environment, as international humanitarian law became implicated in the international campaign against colonialism (a condemnation of Portugal’s continued hold on its territories in Africa), foreign occupation (a move against Israel after its gains in the 1967 Six-Day War), and racist regimes (attacking South Africa’s apartheid system and minority rule in Rhodesia).

The writing of the Additional Protocols is thus remembered by legal scholars and historians alike as an ideological struggle, at least in its early phases. The 1974 session of the Diplomatic Conference that drafted the Protocols – the first out of an eventual four – was an angry and, in the minds of some of its participants, unproductive encounter in which international humanitarian law was forced into the service of political goals. The decision to include ‘wars of national liberation’ in the category of international conflicts was emblematic. Neither the ICRC nor the Swiss government had wished to reopen the Geneva Conventions, fearing that political antagonisms would diminish rather than improve the protections they provided. Nonetheless, like the IHFFC, several of the key protections for medical facilities, transports, and workers are to be found in the Additional Protocols. Amidst the many disagreements aired during consultations, there was a near consensus on the importance of improving protections for medical missions, and government experts were able to make significant headway in agreeing on key provisions.[2] And while certain areas of the law were more likely to be subject to agreement, the discussions as a whole became less inflammatory over time.

What does this earlier example tell us? For one thing, it suggests that the idea of a crisis of international humanitarian law is neither new nor sufficient as a motivator for change. Decolonisation was a crucial factor in debates about updating the law in the 1960s and 1970s. There was widespread recognition then that the large majority of ‘third-world’ countries had not been independent when the Geneva Conventions were written. Since that time, the presence of developing countries in international forums had increased markedly. The desire of some of these states to assert an anti-colonial agenda, including through the use of human rights and humanitarianism, profoundly marked debates about international humanitarian law. This political goal combined with the sense of urgency to strengthen the case for change. In other words, it was the wish to see law take account of the struggle for decolonisation and against racial discrimination – what contemporaries and commentators since have described as a distortion of the law’s impartiality – that created conditions for the law’s ‘reaffirmation and development’.

Of course, this did not lead to perfect law for the regulation of armed conflict. Nor did it guarantee respect for that law in the future. But it reminds us that a diagnosis of crisis, no matter how starkly (or frequently) presented, is not enough to effect change. Less pure motivations for considering humanitarian protections, such as institutional rivalry and political point-scoring, have also played a part in creating sufficient conditions for action. The history of international humanitarian law shows us this, notwithstanding the fact that even the ICRC, with its long experience of brokering agreements on the law, has today resorted to a public discourse of newly pressing crisis. The Kunduz attack may well be used as a symbol of crisis, but crying crisis alone is not enough.

[1] Richard Baxter, Humanizing the Laws of War: Selected Writings of Richard Baxter (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 292. Originally published as ‘Humanitarian Law or Humanitarian Politics? The 1974 Diplomatic Conference on Humanitarian Law’, Harvard International Law Journal 16 (1975): 1-26.

[2] Frits Kalshoven, Reflections on the Law of War: Collected Essays (Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff, 2007), 39-40, 61-65. Originally published in Netherlands Yearbook of International Law 2 (1971) and 3 (1972).

Dr Eleanor Davey is Lecturer in History of Humanitarianism and British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at the Humanitarian and Conflict Response Institute, University of Manchester, and author of Idealism beyond Borders: The French Revolutionary Left and the Rise of Humanitarianism, 1954-1988 (CUP, 2015)