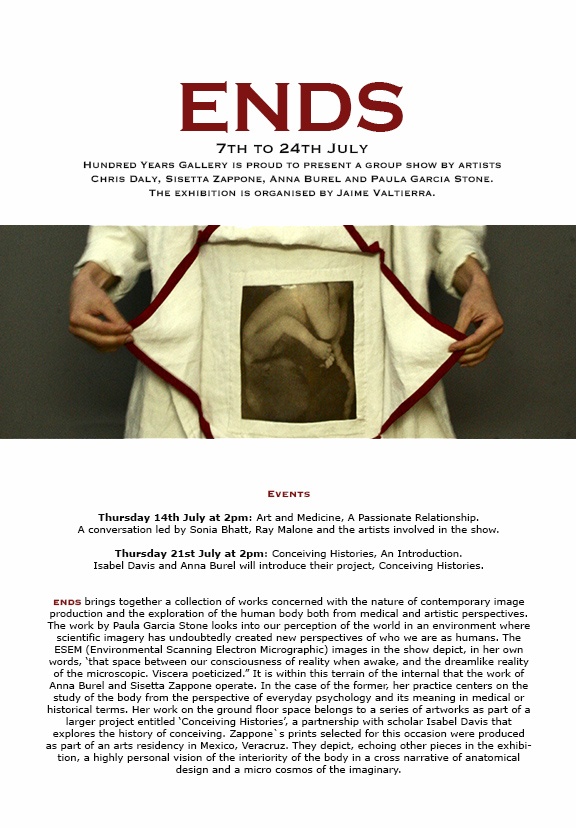

We’re pleased to announce that Conceiving Histories is part of the Being Human Festival programme in November 2016. The festival is a showcase of current humanities research and there is a great programme of events across the country. The theme this year is ‘Hope and Fear’, which speaks directly into the heart of what the Conceiving Histories project is all about.

FREE – book here. When: 23rd November 2016, 6pm-8pm (includes a wine reception).

Where: Senate House, WC1E 7HU. Show on a map.

Hope and fear are projections of the future. Whether hoping or fearing pregnancy, waiting to find out can be difficult. This project looks at what happens in that wait, in the fantasy space before diagnosis – of pregnancy or infertility. How does future projection affect our present? This interest in the present and the future is informed by a study of the past. History, it turns out, is a good way of reflecting on how things are for us and how they could be in the future, a reminder that we are not the first to struggle with uncertainty in our own bodies or in our lives.

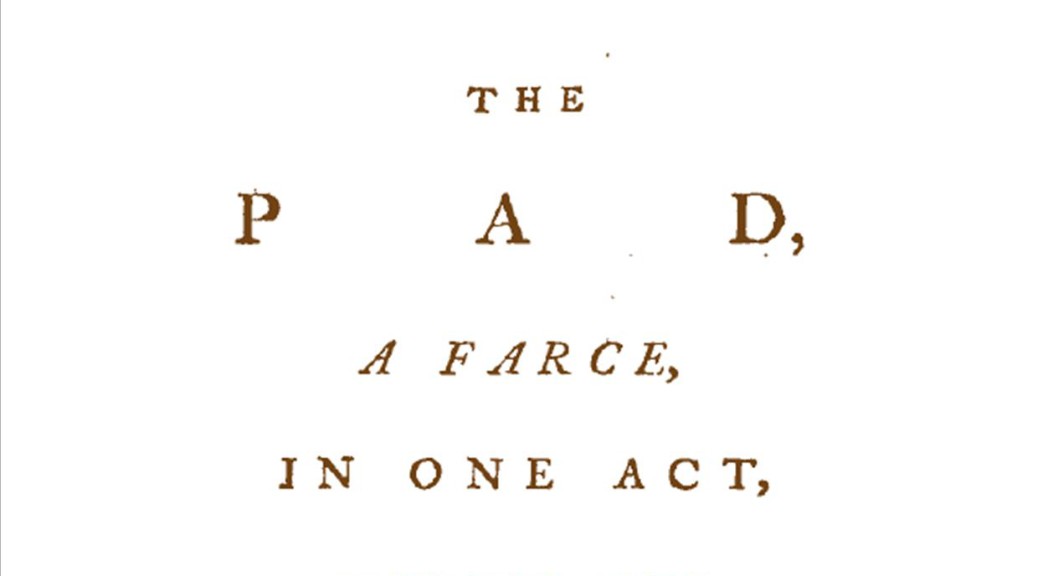

Conceiving histories will be addressing the theme of Hope and Fear in the history of un-pregnancy through two curious case studies. One looks at an odd fashion from 1792-3 for the Pad, a false tummy which simulated pregnancy. Most of the evidence for it is from contemporary satire, like in this image here which laughs at the idea that, with a Pad, anyone – old or young – could be ‘pregnant’ with this new look. Even the little girl on the left is padded and so is her doll.

©Trustees of the British Museum

We look at the ludic celebration of this potentially absurd fashion but ask some serious questions about it. Today maternity fashions are very exclusive. The divide between maternity wear and other fashions is carefully observed. How does this contribute to the other social distinctions we make between women who can have children and those who can’t or haven’t yet? How does this exclusivity make us feel? Can we imagine fashions for today that enable a participation in pregnancy for all? When we look at the comedy in these depictions of this fashion can we reflect on the potential humiliation in not being, or not being able to be pregnant?

Our other case study is darker, responding more to the festival’s theme of fear. It explores an idea for a strange institution, the experimental conception hospital, described in a commentary on a peerage dispute from 1825-6. With high walls and strict staff recruited from nunneries, the hospital would be a secure and secret space in which a hundred women were brought in as experimental subjects. These experiments would solve pressing questions about how to diagnose early pregnancy in an age before reliable pregnancy testing and calculate precisely the length of gestation. What a public service that would be! The experimental conception hospital pr esents a fantasy about the future but one which looks back to the medieval past. Just as our project does, it sees history as key to our reproductive futures. We’ll be looking at this intriguing historical example to think about fantasies of scientific objectivity in relation to the reproductive body and why such fantasies might trigger a return to historic ideas and materials.

esents a fantasy about the future but one which looks back to the medieval past. Just as our project does, it sees history as key to our reproductive futures. We’ll be looking at this intriguing historical example to think about fantasies of scientific objectivity in relation to the reproductive body and why such fantasies might trigger a return to historic ideas and materials.

Isabel Davis and Anna Burel will be discussing these case studies, considering them historically. However, they will also be presenting new artistic responses to them which are helping to shape the Conceiving Histories project. There will be time to ask questions or offer comments on the work presented and a wine reception for more informal conversation.

Everyone is welcome and the event is free but you need to book a place here.

At Senate House, WC1E 7HU. Show on a map. 23rd November, 6pm-8pm.

Please be aware that the artwork in this event tackles the emotive subject of the female body in relation to pregnancy. Some people may find the images that will be presented disturbing. Click here to see the character of the work, although not the specific images involved in this event.

Uncaptioned images: © Anna Burel 2016.

You may also be interested in another event, also at the Being Human Festival:

The Maternity Tales Listening Booth, an interactive installation exploring the spatial history of childbirth. Created by architectural historian, Dr Emma Cheatle, see and hear accounts of homes and midwives in the 18th century and lying-in hospitals in the 19th century. Fill in questionnaires or make recordings of your own experiences of maternity spaces.

Find out more about this event here.