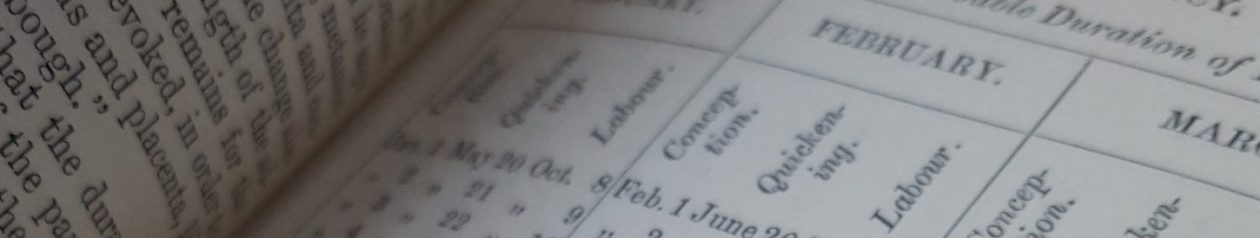

Imagine a dark Gothic building, with walls a hundred foot high. Inside are one hundred female experimental test subjects, ranging in age from fourteen to forty five. The staff over-seeing this curious institution are recruited from monasteries and relied on to keep accurate scientific data. No men are allowed into this hospital, part from male midwives of scrupulous integrity. Their visits are part of a clinical research trial, to discover the exact length of human gestation, and from when and what to date pregnancy.

This is the bizarre science-fictional building imagined by Robert Lyall, who was a nineteenth-century physician, botanist and traveller, in response to the confusing medical evidence presented in the Gardner peerage dispute heard in the House of Lords 1825-6.

This story testifies to how difficult it sometimes was for historical physicians, let alone lay people, to diagnose pregnancy reliably and early. The medical evidence gives us all sorts of information about how pregnancy was dated at the beginning of the nineteenth century, showing that there was little agreement between practitioners about the best way to do it. Just like today, people in the early nineteenth century understood themselves to be living through a hypermodern age, when all sorts of strides were being made in technology and science: for example, in steam power, electricity, and air flight. And yet, for all this progress, it still wasn’t possible to get a fix on the reproductive body, which was so familiar and close to hand. It felt anachronistic, Robert Lyall tells us in his eccentric commentary on the Gardner case.

We might reflect on a similar feeling of anachronism that people, and particularly women today encounter in the two week wait, in the time after embryo transfer or ovulation and before a pregnancy test is reliable. Just as women search their bodies for pregnancy signs and symptoms, Robert Lyall speculates on whether conception would feel like ‘the sting of a wasp, or like the bite of some other insects’. But, in the time before it’s possible to test, women today are in the same position as those in the past who didn’t have the test at all.

Watch a short video made by Anna Burel, which sets Robert Lyall’s words to images, and evokes the hospital’s inmates.

Featured image:

Anna Burel, 99, 76, 12, 93, 7, 22/100 (2016).