With a focus on housing and public space, the first of three sessions co-organised by the ICA, the Architecture Space and Society Centre at Birkbeck (ASSC), and the Consortium for the Humanities and the Arts South-East England (CHASE), brought together practitioners, theorists, activists and students to try and answer what might at first seem like a trick question. ‘Where is the social in Architecture?’ Surely the answer is ‘everywhere’? After all, is there any aspect of architectural space and architectural practice which is not thoroughly social? Below is the blogpost Alistair Cartwright wrote following the workshop.

While Foucault once decried the ‘pious descendents of time’ from Kant to Marx, who in revealing the contradictory dynamics of historical development tended to treat space as a passive backdrop, today we’ve become much more used to thinking of space as socially constructed and constructing. So if we have to ask where is the social in architecture, maybe it’s less because the social and the architectural have come unstuck, and more to do with the maligned nature of the social itself.

Margaret Thatcher’s famous declaration ‘there’s no such thing as society’ went hand in hand with a systematic demonisation of spaces that strived not only to actively shape the social, but to celebrate its everyday glory too. As Kate Macintosh pointed out in the opening talk of the day, the public housing of the 1960s and ’70s was a particular target in this respect. Brutalism’s ‘streets in the sky’ – originally conceived as staging grounds for neighbourly chatter and children’s games – were singled out in the 1980s and ’90s as ungovernable zones harbouring criminal behaviour. Dawson’s Heights, the public housing project in East Dulwich that Kate designed in the mid ’60s, made brilliant use of connecting walkways to provide a courtyard-like enclosure to the estate’s central green space. Those walkways were removed in the 1980s in line with the ‘designing out crime’ ideas of the day. Yet while Dawson’s Heights has had its fair share of problems, it has survived management changes to become, by many accounts, a much loved housing estate among residents.

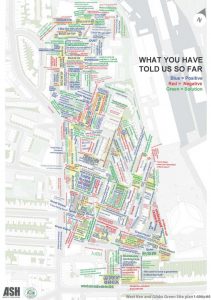

In the contemporary context, private developers desperate to capture the valuable land occupied by post-war estates continue to make effective propaganda out of such ‘liminal’ spaces as walkways and courtyards. Geraldine Dening, co-founder of Architects for Social Housing (ASH) and our second speaker of the day, showed how political self-organisation by residents can combine with architectural thinking to push back against the destructive tendencies of the property system. ASH’s work in support of the bid by West Kensington and Gibbs Green Estate to become a resident controlled housing association used walking tours to map out the complexity of opinions surrounding the estate, while drawing them together in support of a clear consensus against demolition and in favour of refurbishment. The result was a ‘people’s plan’ that identified options for infill housing, rooftop extensions, conversion of underused garages, and improved gardens and community facilities. The results turn the sometimes obscure tools of architectural analysis towards a critique of regeneration plans by the developer Capco, while offering an effective alternative to demolition.

Clear sympathies over the far-from moribund status of the social and its centrality to architecture link Kate’s and Geraldine’s practices. Still, the days when councils and government employed 50% of all architects can seem very far away indeed. While municipal architect’s departments like that of the London County Council were once widely recognised as powerful agents of regulation, planning and design, today’s architect is, as Kate Macintosh put it, caught in a ‘Byzantine labyrinth of management structures’. It is perhaps this web of developers, project managers, quangos, contractors and sub-contractors that today forms the primary nexus of ‘the social’ in architecture. Little wonder then, that so few of the architecture firms approached by ASH are willing to involve themselves in reputationally risky projects. As well as diluting responsibility for critical safety issues, among other things, the complex social networks which architecture participates in have powerful monitoring and censoring effects.

Following on from this, Samir Pandya’s presentation dealt directly with the question of how architectural agents – be they designers, writers or researchers – are effectively socialised. Focusing on the question of architectural pedagogy, Samir walked us through a sample of his projects with students at the University of Westminster. From mapping intercultural exchanges across the divided city of Nicosia in Cyprus, to projects that asked students to examine the spatial construction of their own identities, Samir’s teaching practice tests the limits of what we traditionally think of as architecture, while seeking to equip a new generation with the skills and awareness to engage critically with the discipline.

Critical mapping in Nicosia

Drawing on postcolonial thinkers such as Homi Bhabha and Gayatri Spivak, an architectural pedagogy in this vein aims to encourage ‘virtuous self-doubt’, questioning the architect’s privileged role in forging visions of the material future, and dwelling with the notion that to ‘concretise’ an idea which claims to express an identity is always, at some level, a violent act.

Leave a Reply