This blog post is penned by Dr Leslie Topp.

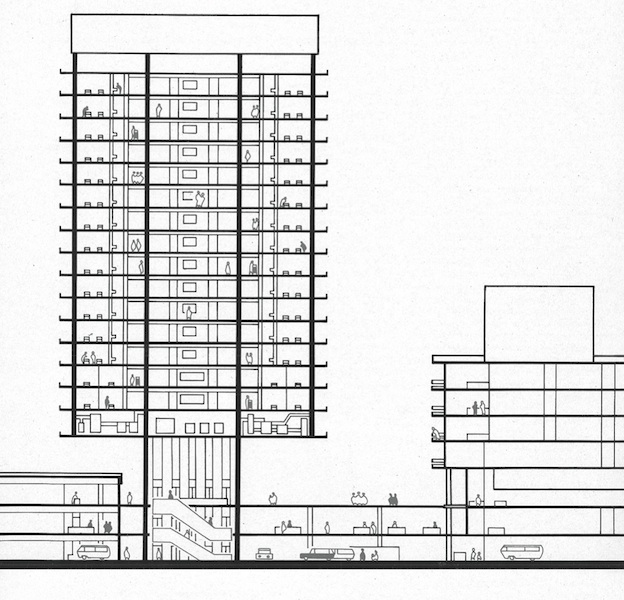

The cover of Healing Spaces, Modern Architecture and the Body, a collected volume published in 2016 by Routledge, features an architectural cross-section. A rectilinear tower with a reinforced concrete frame is rendered as a grid of pristine logic and perfection. Within the grid’s compartments, miniature outlines of sexless human figures gather in small groups in corridors, push trollies, or attend to patients. The patients – for this is a rendering of a hospital designed by Heinle, Wischer und Partner for the University of Cologne in 1966 – are only indicated by the presence of identical pairs of beds occupying the outermost compartments of the grid on each floor. This is architecture as a ‘machine for healing’ (to use a phrase from the late 18th century, popularised by Foucault), an orderly framework in which the disorder of the sick and suffering human body is rendered invisible.

The tensions between the built environment, architectural ambitions and bodily health and sickness were at the centre of a New Books event on 3 February, co-organised by the Architecture Space and Society Centre and the Centre for Medical Humanities. We were delighted to be joined by the book’s editors, Sarah Schrank (California State University at Long Beach) and Didem Ekici (University of Nottingham), who introduced the book, and gave papers based on their chapters, followed by a brief response from me (standing in for Caitjan Gainty, KCL, who very unfortunately was ill and couldn’t join us) and a lively Q&A.

Didem Ekici’s paper explored the German mid-late 19th-century pre-history of the modernist preoccupation with light, air and clean surfaces. She introduced us to the first person to hold the post of Professor of Hygiene, Max von Pettenkofer. Pettenkofer’s highly influential writings envisioned the dwelling as an organism, an extension of the human body, which had a crucial impact on the inhabitants’ state of health. Quantity of fresh air per person, the quality and intensity of light, structural and decorative materials and their mould-generating and dust-retaining properties – all these were recorded and analysed in a highly normative and rationalising effort to transform the dwelling in the context of widespread anxiety about the city.

Sarah Schrank took us to the American suburbs of the 1930s-60s, and focused on the subculture of nudism there. Architects worked with clients practicing domestic nudism who wanted to tailor the newly emerging house types of the time (the ranch, the split level) to their need for privacy and concealment. So the picture window looked into a small room walled off from the rest of the house, and a vestibule allowed unexpected guests to be kept waiting for a few minutes while the family pulled on some clothes. At the same time, the back of the house and the garden were opened up to the maximum possible extent to sun. There was a moment around 1960 in which countercultural forces and vernacular architectures came together to create an original and liberating environment. The increasing sexualisation of the nude body and the impact of a growing pornography industry (for which the suburbs were a provocative setting) led over time to a marked change in tone.

Discussion included questions of the institution and ‘the institutional’ (that is, the long-standing suspicion that hospital buildings can themselves make people unwell, institutionalising them in unhealthy ways). We explored the complexity of mind-body links in modernist thinking. We also broached the contemporary politics of wellness, in which social issues are made into questions of individual responsibility and blame/shame, and the role that nuanced contextual studies of the spaces of health can play in revealing such assumptions as constructs.

Leave a Reply